Cotton market update

Pete Johnson, Left Field Solutions

About the Author: Pete Johnson is partner in Cotton Compass (a subscription based market information service) and runs Left Field Solutions (an independent cotton and grain cash brokerage business based in Toowoomba, Queensland).

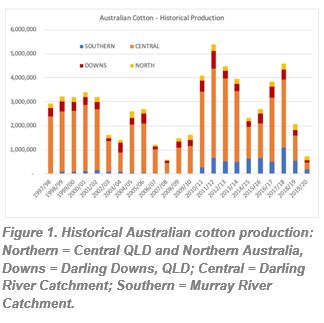

From a market perspective, the timing of the current scaled expansion of cotton production in Northern Australia perhaps couldn’t be better.

An historically small crop in Southern growing areas should provide domestic support to cash values as growers in NSW and Southern QLD look to cover in shortfalls against existing forward sales commitments.

At the same time, there are emerging quality issues elsewhere in the world that are casting doubt over what the global high-grade situation will look like as we head deeper into 2020 – a situation that should support the price international mills are willing to pay for good quality Australian cotton.

This all, of course, needs to be balanced against a challenging macro-outlook, particularly concerning the US/China trade war and what has to date been its’ negative impact on global business – and thus our spinning mill customers’ confidence.

Overall, however, for new growers in a new area, the domestic situation will likely be the over-riding supportive market influence for the next few months at least, and will reduce the “need” to forward sell anything until you are more confident over production. Perhaps it’s a case of don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes - or bolls if you prefer.

And importantly also – this is the kind of market situation where everything is not always as it appears. In early November, for example we were seeing fresh sales from some growers at A$610/bale FOT ginyard (in order to replace bales other growers now knew they couldn’t produce). This was at a time when the generic “published” market (based off export parity) was only around $585/bale. That $25/bale price difference isn’t due to any kind of subterfuge from the merchant’s perspective, it’s just that this is, and will likely remain, an illiquid market – and these “washout” opportunities are not readily available in chunky volumes.

That said, whilst the domestic “washout” market is illiquid, we think it has some longevity, and should be well supported until growers in the south gain confidence over their production - and particularly that proportion of their production that remains unsold. And with our own Cotton Compass estimates suggesting perhaps 70 per cent of an estimated 750,000 bale national 2019/20 crop has already been committed to merchants, we doubt there will be a large volume of southern cotton come to market until perhaps February next year.

Global High Grades Could Get Tight: Additionally, as mentioned above, there are growing concerns about potential supply tightness of high-grade cotton globally. This is the market segment most Australian cotton tends to play in, and the generally excellent quality results the last few seasons in the Ord and Katherine suggest Northern Australian production should be no different. Elsewhere in the world, however, the late and excessive monsoon in India appears to be creating quality issues as we write, and at the same time we are hearing of staple length issues as harvest progresses into Texas in the USA. Meanwhile, the crop in China’s main high-grade producing province, Xinjiang, is smaller than earlier expectations, and the 2018/19 Brazilian crop is already heavily committed – particularly the high-end portion.

When combined with the prospects for a tiny Australian 2020 crop harvest, it really feels like this global high-grade position could get squeezed as we head into Q2 and Q3 next year (i.e. during our harvest and ginning season and before Northern Hemisphere new crop hits the market).

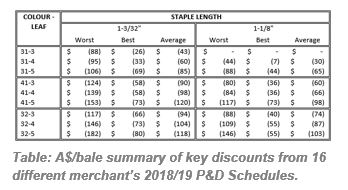

Quality Will be Critical: In this environment, we could see a two-tiered market develop – one where merchants are willing to pay significantly more for high grade cotton than they are for “out of spec” bales. If you do decide to forward sell, this means you will need to pay particular attention to Premium and Discount sheets, as they do vary significantly (see table below).

This raises an interesting point. When buying forward, merchants use three main parameters to determine the “base grade” price to the grower: 1.) Colour Grade = Middling (31-3); 2.) Staple = 1-1/8” (36) and; 3.) Micronaire = G5 (3.5-4.9). Premiums and discounts (P&D) are then allocated for other grades. This base grade, however creates a disconnect, because by far the majority of the forward sales the merchant then makes to a mill are of a higher quality, normally Strict Middling (21-3), 1-5/32” (37), G5.

So….If you decide to hold back on selling all or a portion of your cotton until after it is ginned and classed, you need to be aware – particularly in the current environment – that 31-3, 36, G5 cotton (or similar) once classed may not be worth nearly as much as it might have been if delivered forward against a P&D schedule. By the same token, there may be some lower grades that “outperform” the P&D if held back for sale after classing. This is, however, more likely in a year where low grades are in tight supply globally (rather than high grades). It is simple supply/demand theory, and every year will be different.

A stressed dryland crop, or a crop with late rain on open bolls or defoliation problems may be more at risk of quality discounts.

Unusual Times: The current market set-up, particularly concerning the short domestic crop won’t always be the case – in fact, with 100 per cent of our crop exported, usually domestic supply conditions play very little part in determining Australian cotton market direction.

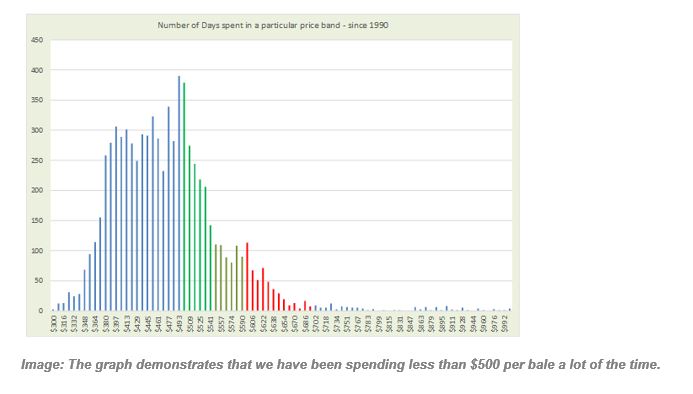

Exposure to the vagaries of global supply and demand for what is, in effect a discretionary commodity, make cotton markets perhaps even more volatile than other agricultural sectors. From a historical perspective, it is not unusual to see this market move by A$100-150/bale in a 12-month period.

When combined with the fact that most gins typically do not provide warehousing facilities and require bales to be moved within short time frames once processed – this has led to the development of a well established forward market, that allows a wide time window for growers to manage their price risk ahead of ginning (rather than after it).

Normally, this is done in a “staged” approach with maybe 20-30 per cent of anticipated production being sold at any one time - depending on current price and price outlook.

For example, the chart at the end of this article demonstrates the period of time that price has spent in a particular price band since 1990. What this shows is that historically, price has only been above $600/bale for about eight per cent of the time, and above $550/bale 35 per cent of the time - and that there is a large chunk of time that we actually have spent below $500/bale!

So, in the context of history, these are currently very good prices…so may warrant forward sales particularly if you have some production certainty and see some downside risk to price.

Forward Marketing Strategies: As new growers, in a new production environment, it will obviously be sensible to take an extremely cautious approach to forward marketing given both your production and quality risk are largely unknown. And remember, the main aim of any forward marketing plan is to protect your bottom line – not destroy it!

Depending on the scale of your operation, and your level of confidence, a fairly “risk averse” marketing plan might look something like the following (and please bear in mind that this is an example only, not a recommendation!!!):

- Sale 1: Sell to a maximum 25 per cent of “Safe Anticipated production” at first open boll – but ONLY if cash price is above A$575/bale FOT ginyard;

- Sale 2: Sell to a maximum of 50 per cent of “Safe Anticipated production” at 80 per cent open – but ONLY if cash price is above A$575/bale FOT ginyard;

- Sale 3: Sell to a maximum of 75 per cent of “Safe Anticipated production” at picking – but ONLY if cash price is above A$575/bale FOT ginyard;

- Sale 4: Sell a balance of crop once modules are delivered to the yard and weights known – but ONLY if cash price is above A$575/bale FOT ginyard;

- Sale 5 (if required): Sell any unsold bales post ginning and classing via “tender” based on known qualities.

But, if this looks a bit too hard - or looks like it will keep you up at night – then maybe your best option is just ignore Sales 1-3 and only consider entering the market once your modules are in the ginyard and production is effectively known. Obviously an irrigator will have more confidence over production potential than a dryland producer – season dependent. Everyone will be different.

The key thing is that there are plenty of people to talk to. Other growers and agronomists to get an idea of production potential and quality risk, merchants and independent brokers to get an idea of market direction and counterparty selection (particularly regarding P&D sheets).

Just take your time – in the current environment it doesn’t feel like there is any need to panic into marketing decisions.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!