Understanding the rainfall forecast for summer 2020

A senior climatologist explained that it will always be difficult to predict rainfall in places like Central Australia, because we are right in the middle of the continent. The moisture for rain comes from the oceans, and by the time it has travelled over our vast, hot, dry continent it is difficult to say how much moisture will be left. Wind speed and direction, temperatures and frontal systems will all influence how and when the rain falls.

What we do know is that the global climate drivers such as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) are very good indicators of how much moisture is likely to be available for local weather systems to tap into. As the name suggests, the IOD relates to conditions in the Indian Ocean, while ENSO describes conditions in the Pacific Ocean. If there is a good source of moisture, then obviously there a better chance of moisture-laden air making it to Central Australia. It’s worth paying attention to the status of the climate drivers.

From about September 2019 until January 2020, Central Australia experienced one of the hottest, driest summers on record. This can be largely attributed to the very strong, positive IOD that persisted until nearly the end of January 2020. It’s worth noting that once the IOD broke down, the rainfall in late January to March was much closer to normal for many areas in the region. ENSO was neutral for the summer of 2019-20.

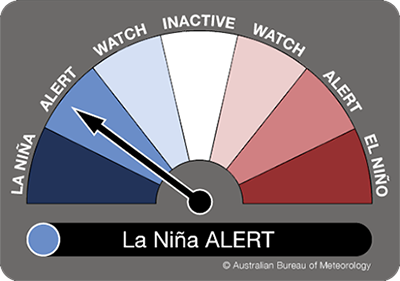

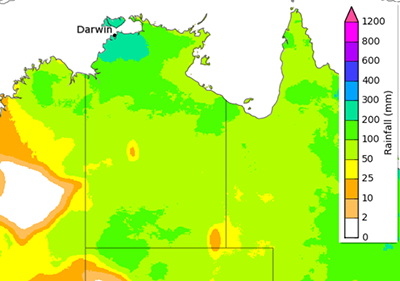

As we approach the summer of 2020-21, most of the global climate models suggest that a La Niña event will form in the equatorial Pacific by about October. The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) has issued a La Niña alert (Figure 1) which means there is a 70 per cent chance of a La Niña event forming in the coming months. La Niña is often, but not always, associated with wetter than average conditions in Central Australia. It also increases the chance of getting useful rain in early summer. In the past, some La Niña events have meant increased rain in eastern Australia but Central Australia missed out. On the other hand, all the really wet years in Central Australia (such as 1974, 2000 and 2010-2011) were La Niña years. Figure 2 shows the outlook scenario for the period September to November 2020 (as of 13 August 2020). For many properties, February is historically the wettest month of the year on average. An early start to the season increases the chance of achieving maximum pasture growth if effective follow-up rain events occur.

Left: (Figure 1) The Bureau of Meteorology have issued a La Niña WATCH indicating the chance of La Niña forming in 2020 is around 70%— roughly three times the average likelihood. www.bom.gov.au.

Right: (Figure 2) Rainfall totals that have a 50% chance of occurring for the period September to November 2020. www.bom.gov.au

Extended or prolonged growth events are rare but extremely important in Central Australia. Many of the perennial pasture species will only germinate and establish strongly under these conditions, making it a critical time for looking after land condition.

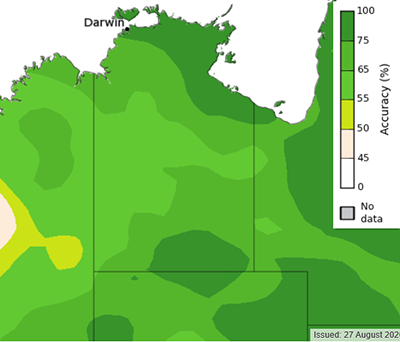

There is always some uncertainty in the climate forecasts, in fact, all BOM forecasts have a ‘skill’ map attached so you can see the historical accuracy of the forecast (Figure 3). Having a general understanding and awareness of the global climate drivers definitely provides useful information for pastoral managers.

(Figure 3) Historical skill for rainfall forecasts for the period of September to November. www.bom.gov.au

Management implications for a La Niña event

After such a prolonged dry period, a lot of perennial grasses have been weakened or may have died. Seed stores for annual grasses are also likely to be very low. A La Niña event could allow for excellent pasture recovery, provided that grazing is managed to ensure seedling establishment and seed production. The first priority is to allow germinating plants time to mature and set seed prior to grazing. Grass seedlings are like calves, they need to be protected, fed and watered regularly so they can grow to their full potential. A strong, mature perennial grass tussock has the potential to survive for ten years in the landscape, sometimes for much longer, but only if they get a good start – much like a quality heifer!

There are bills to pay

When production has been low for a while, there is a lot of pressure to capitalise on pasture growth. Sometimes it is easy to see that changes need to be made but it can be difficult to know where to begin. Starting small might seem more achievable and affordable. If there are good rains from a La Niña summer, some management options for 2020-21 might be to:

- Spell only the most productive paddock

Got some really sweet country and it’s all in one paddock? Destocking this paddock could boost land condition and production for years to come.

- Implement a two-paddock rotation using existing paddocks

Muster two paddocks. Keep only the very best genetics and sell the rest. Put the retained herd in one paddock only, ensuring safe carrying capacity is not exceeded.

- Turn off selected watering points

In very large paddocks, turn off the water point closest to the most productive land type to help reduce grazing pressure.

- Build a fence

Look at existing land types and infrastructure. Some locations lend themselves to fencing off sweet country for a summer spell.

- Keep only the very best stock.

Retain only quality breeders. Aim for a higher calving rate and improved weight gains.

Above: The photo on the left is from 2006 and the photo on the right is from 2014. These years had similar rainfall (close to the median of 240mm) but improved land condition led to an increased pasture response in 2014. Spelling during the 2010-2011 La Niña event was the catalyst for the land condition improvement. Photos: C. Materne.

What if it is only one good year?

Avoid the trap of allowing your herd to eat everything in sight. Leaving some grass in the paddock is not wasteful from a production viewpoint as pasture grown in Central Australia has the unique advantage of retaining its nutritional value for up to two years. That means you have production this year and production next year. If all your grass gets eaten in the first year, then you are back to square one, perhaps even worse off because you ‘used’ the seeds for this year’s germination but didn’t give plants the opportunity to produce much new seed.

Take-home message

Stocking rate decisions made this year could ultimately determine long-term land condition for paddocks/stations. Pastures have taken a hit in the past few years and it is important they are given the opportunity to recover when it rains. Now is the time to plan how you’ll ensure the 2020 seedlings grow up to be your most fertile and productive grasses!

More information

For more information on pasture growth and seasonal outlooks for Central Australia, subscribe to the quarterly NT Pastoral Feed Outlook.